Vogue USA - Happy Valley

In his native Italy, garden designer Luciano Giubbilei has created a verdant oasis that grows under the Tuscan sun.

Marella Caracciolo Chia

Aprile 2018

In his native Italy, garden designer Luciano Giubbilei has created a verdant oasis that grows under the Tuscan sun.

As a teenager, Luciano Giubbilei worked after school as a delivery boy for a florist in his native city of Siena, Italy. He also baked bread at a local bakery, repaired the city’s rooftops, and, as soon as he got his driver’s permit, worked as a truck driver zooming all over Tuscany, his camera always at hand to record what caught his eye: the winding roads flanked by cypress trees, the lunar hills of the Crete Senesi, the wild vegetation along the autoroutes. Fast-forward three decades and Giubbilei, now 46, is an acclaimed garden designer based in London with projects that have sprung up all over England, Europe, the U.S., and Morocco. Nothing has seemed out of his reach except, ironically, being hired to design a garden in his own country, Italy. Then, three years ago, that elusive dream finally materialized.

“This landscape is in my bones,” says Giubbilei, who has the classical features and shy charm of a Ghirlandaio portrait. Val d’Orcia, in southern Tuscany, is the setting for a roughly four-acre garden commissioned by a pair of new-minted wine producers. Over a cup of oolong tea beneath the shade of a majestic oak tree in the garden’s vast central courtyard, Giubbilei traces his love of landscape back to his childhood. When his mother, a hairdresser, and his father, a driver, moved to the outskirts of town with his older sister, they left Luciano, age four, in the care of his grandmother, a seamstress who lived in the city center. “It was strange, not living with my parents, but I was happy,” he says. Growing up, he played soccer, but he says he didn’t “fit in” at school. “I couldn’t sit still in class and had no discipline.” Always a daydreamer, he would regularly ditch classes and wander off into the Siena countryside. “Surrounded by nature, I felt protected,” he recalls.

His path to becoming a gardener was filled with coups de foudre. “My life changed thanks to a love story,” he muses. He was eighteen when he met a young Englishwoman studying art history in Siena. Together they moved into a house outside town that was cheap to rent and where he could grow their own food. Luciano spent his spare time assisting Silvano Ghirelli, head gardener at the historic Villa Gamberaia in Settignano, near Florence. “One day, Silvano showed me a book of black-and-white photographs by Balthazar Korab that was a catalyst for the way I make gardens,” Giubbilei says. “‘You have to study,’ Silvano told me, ‘otherwise you will end up spending your life inside a single garden, and never find out what the world has to offer!’”

At 21, Luciano moved with his girlfriend to London and enrolled at Belgravia’s Inchbald School of Design, where he graduated as Student of the Year. The love story eventually ended, but he stayed on and took a job with a florist. Clients were so enchanted by his imaginative bouquets that they commissioned him to redesign their terraces and city gardens. In 1997 he founded his own landscape-design studio. Giubbilei has developed a line of outdoor tables and seating with the sculptor and furniture-maker Nathalie de Leval, and is passionate about ceramics. He recently bought a former ceramist’s house in Majorca and plans to make it available for artists in residence.

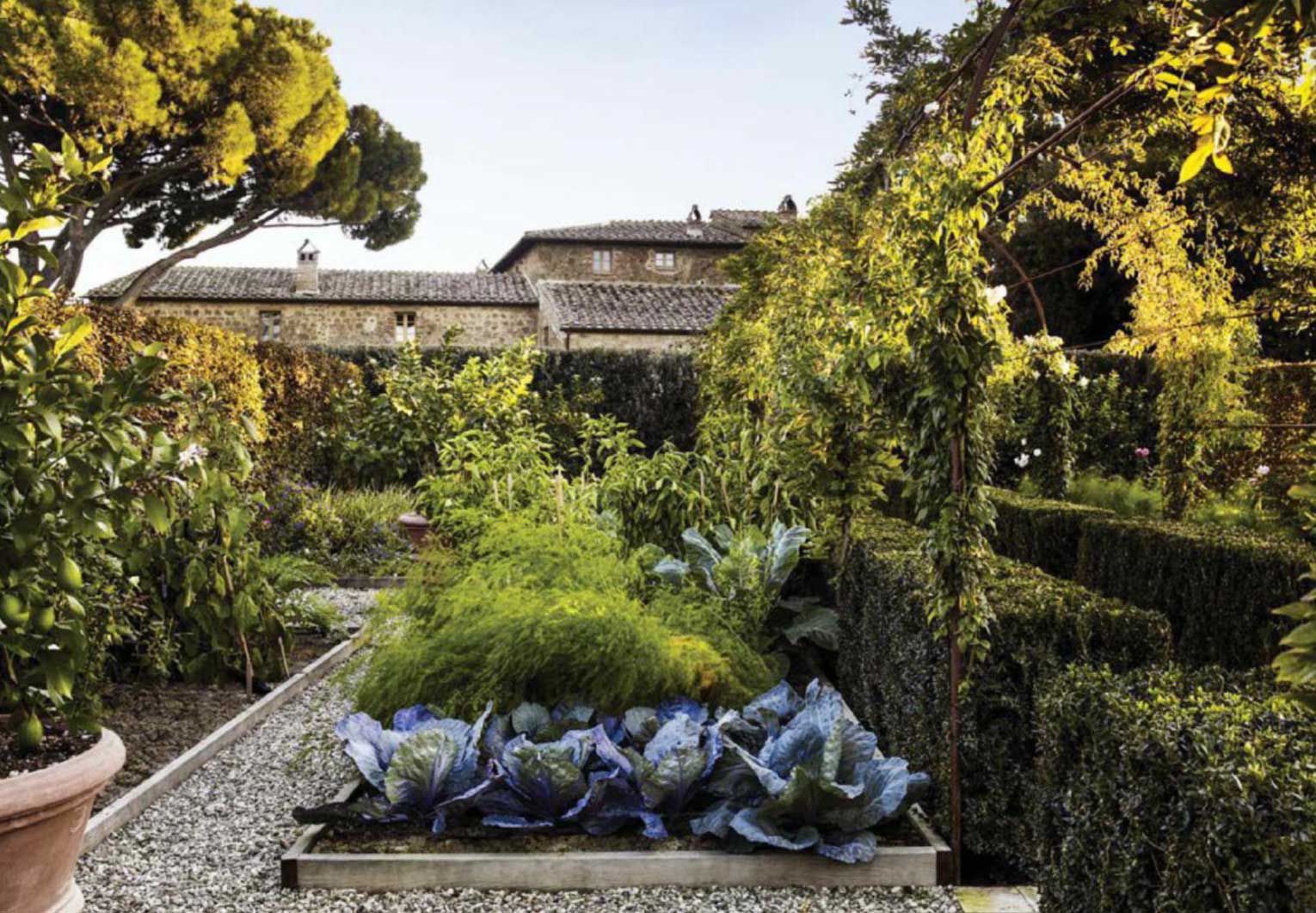

To those familiar with the starkly architectural style of Giubbilei’s early projects, his Italian garden will come as a surprise—or rather, a succession of surprises, since it is planned as a series of “rooms.” The first is a grandly conceived vegetable garden enclosed by hornbeam hedges. Entered through a small iron gate, its patchwork of spaces brim with a controlled abundance of Tuscan vegetables interspersed with English roses, peonies, and delphinium. A steel basin filled with running water reflects the light and creates the timeless sound of abundance. Paved pathways in hand-cut stone lead to a central pergola covered with white wisteria and more roses. Though Giubbilei says he took inspiration from the English vegetable-garden tradition, there are evocations here of the medieval enclosed garden, or hortus conclusus, that plays an important symbolic role in Renaissance painting and poetry.

The courtyard, punctuated by pots of hydrangea and the rotund shapes of clipped boxwood, separates the vegetable garden from the facade of the property, a large fifteenth-century stone building that once served as an ironmongery. “When I first came here,” says Giubbilei, seemingly oblivious to the house’s large white Maremma sheepdog nibbling a piece of apricot crostata from his plate, “I spent days exploring every corner, struggling to get a sense of the place. Finally, at sunset, a golden light fell on the trunk of this oak tree and on the stone wall next to it. That moment of splendor was my gateway to the project.” Dominating the yard are two evergreen oak hedges planted at a slant to evoke a theatrical backdrop. The controlled drama pays homage to Pietro Porcinai, the twentieth-century Florentine gardener whom Giubbilei acknowledges as a major inspiration.

A third outdoor room at the east of the house is filled with Mediterranean aromatics and a free-spirited mix of flowers, including salmon-colored hollyhocks, irises, and pink cistus. Witness to Giubbilei’s education in the English floral tradition, the planting came out of a personal crisis in 2011, when he was at the peak of his success. “I had lost my direction. Despite all the work, traveling from one project to another, I felt stuck,” Giubbilei recalls. “What I missed most were the day-to-day challenges of being immersed in nature.” For guidance, he turned to Fergus Garrett, head gardener at Great Dixter, a medieval manor house restored and augmented by Edwin Lutyens in the early twentieth century. Thanks to the dedication of the plantsman Christopher Lloyd, who inherited part of Great Dixter, it is a place of pilgrimage for horticulturists. Garrett, who understood Giubbilei’s quest to get back to basics, gave him an area to experiment with. He paired him with talented gardener James Horner, who has since become one of Giubbilei’s closest collaborators. “I moved away from a more formal approach to gardening and began to appreciate the seasons’ mutations. In other words, I learned the one fundamental virtue for a gardener: patience.”

One of the perks of the Tuscan project, for Giubbilei, was becoming reacquainted with the familiar places of his childhood. One was La Foce, the estate of the author Iris Origo, now owned by her daughter, Benedetta. Its garden, started in 1925 by Iris and the English designer and architect Cecil Pinsent, is a source of continuing inspiration for Giubbilei. “He comes to visit regularly,” says Benedetta, “One evening he sat alone at the end of the garden and observed every detail as it became dark, trying to conjure how Pinsent had seen it. Only an artist thinks like that.”

Giubbilei’s Italian garden is still a work in progress. He is planning a possible collaboration with James Hitchmough, professor of horticultural ecology at the University of Sheffield, to include a wildflower meadow and sowing seeds in situ using low-nutrient, sand-based soils that require minimum maintenance. He is anticipating a spectacular blossoming next spring. Many other new wonders, Giubbilei assures me, are in store. “If you don’t like surprises,” he observes, “you’d better keep away from gardens.”

A wisteria-covered pergola soars over the path bisecting the vegetable garden.