The World of Interiors - Jilt Complex

JILT COMPLEX

Waiting for the return of his fiancée, who was working away from home, Karl Junker – once a promising artist – began building a sprawling carved-wood house for their life together in the German town of Lemgo. But his betrothed never returned, abandoning him without a word. The house became his life’s work – a strange shrine to a lost love, its murals and cradles a tribute to the family he never had. Text: Barbara Stoeltie. Photography: René Stoeltie. First published: Feb 1995

It could be the plot of a 19th-century melodrama. A young painter leaves the small town where he was born to seek his fortune abroad; he eventually returns home and falls in love with a local girl. He asks her to marry him. The girl has to leave the country and promises to return before long. But she never does.

All the painter’s letters are returned to him unopened. He has already built and furnished a house for his future wife and has even installed a cradle in the nursery for their future firstborn. Overwhelmed by melancholy, he eventually goes mad and dies.

Soppy melodrama? If you like. Above all, it’s a tale far removed from our own time. Yet this was all the real-life story of Karl Junker, a native of the little town of Lemgo in North Rhine- Westphalia in the heart of Germany, who would astonish the world by creating one of the strangest and most fanciful houses imaginable.

Junker was born in 1850, the son of a master blacksmith. Both his parents and his brother died when Karl was still a boy, so he was brought up and educated by his grandfather. After learning Latin he was apprenticed for a year to a cabinetmaker, then completed his military service in Munich before enrolling in the city’s academy of fine arts. His talent won him prizes, and he embarked on a study tour of Italy, visiting such places as Florence and Venice. He seemed destined for a bright career as an artist, but it was not to be. He returned from the land of Michelangelo and Veronese ten years later with only a sketchbook. His early promise seemed to have evaporated but he still saw himself as an artist and held his head high. Re-entering the provincial life of his home town, he soon found himself a fiancée. Unfortunately, the girl had to leave for a while – only a year – to work as an au pair for a rich family in Holland. There was a tearful farewell, but Junker didn’t plan to waste the time before his true love’s return.

In 1889, Herr Junker, now 39 years of age, made an official request to the authorities of Lemgo for permission to build a house. He wanted a home of his own in which to live with his future wife and, if possible, masses of children, whom Karl loved. In his application he stated that he wanted to decorate the façade in several colours, adding gilt in certain places, and that for the interior he envisaged ‘walls and partitions with sculpted motifs and mural paintings’. It was clear Junker was aiming high. When he soon learned that his fiancée’s return would be later than originally planned, he also had time to engage a carpenter to carry out the main structural work.

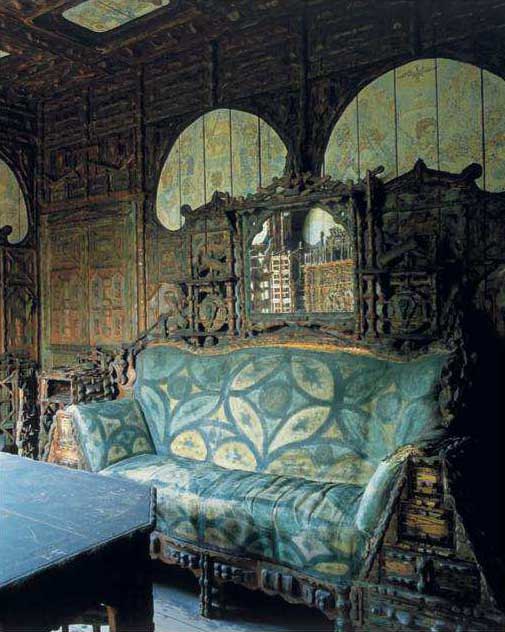

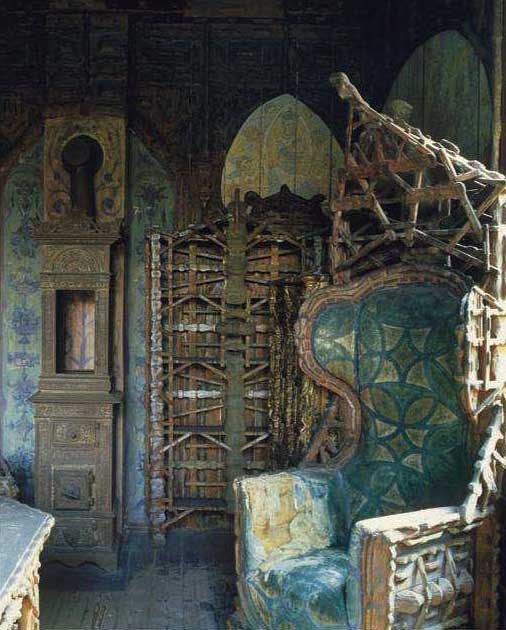

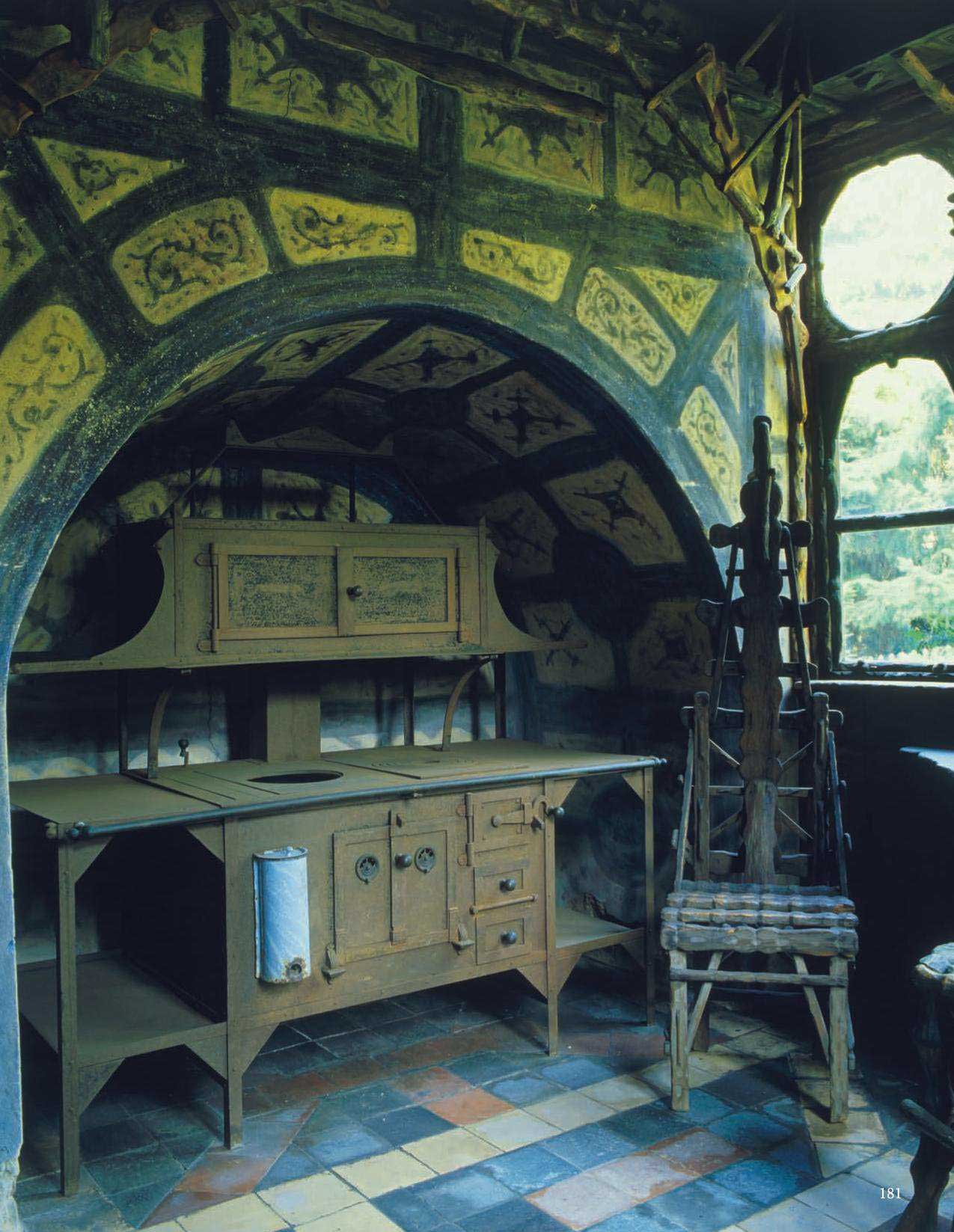

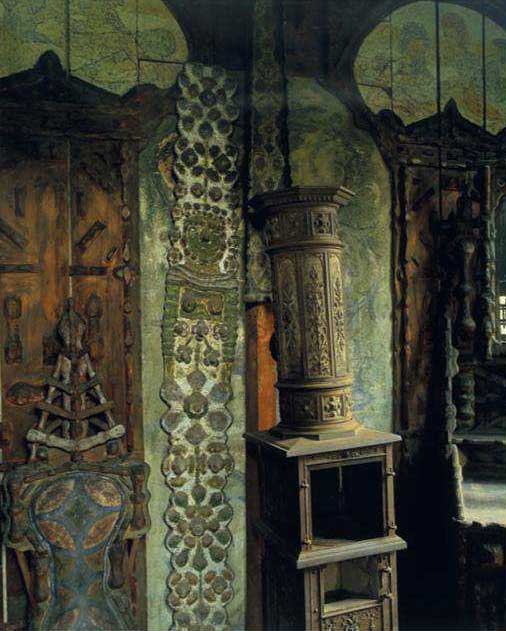

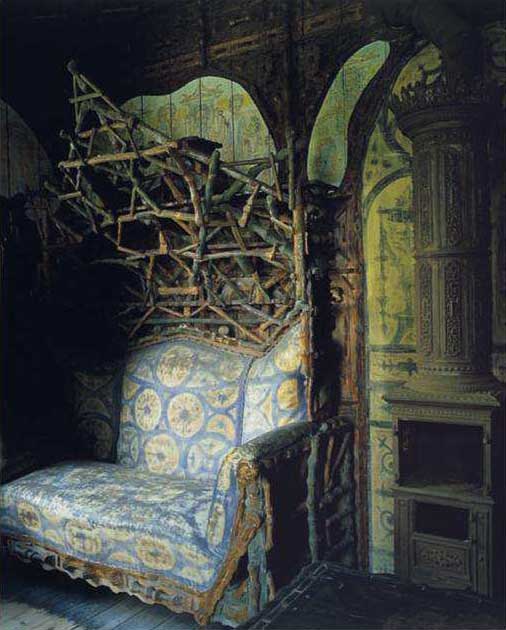

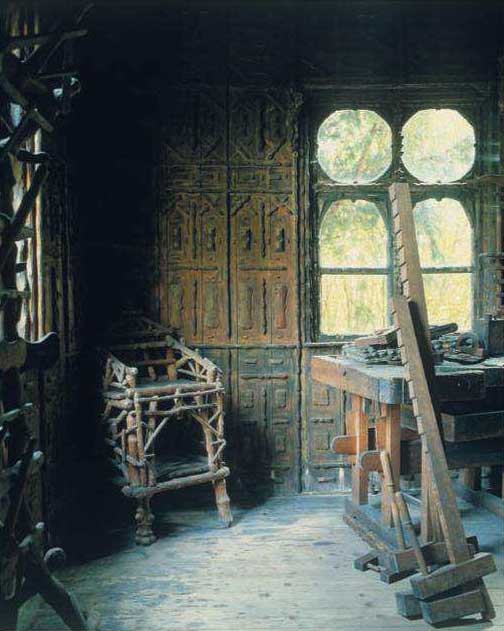

On the ground floor, a corridor leading to an antechamber, a studio and a kitchen took shape. On the first floor, which was served by a generously proportioned staircase, there was a broad salon, a dining room, a master bedroom and two further bedrooms for children. And on the top storey Karl Junker installed several guest-rooms, an attic and a tiny belvedere. The house was furnished with tables, chairs, beds and cradles, all made with Junker’s own hands. He decorated every square inch of the house – down to the floorboards and the upholstery – using a bluish paint that he applied in touches, creating geometric motifs and emphasising details. There were a number of cast-iron stoves and, at a time when most of Lemgo’s inhabitants had to be content with outside loos, Herr Junker went so far as to install one inside, behind the vestibule and close to the entrance.

This was true luxury; he devoutly hoped it would meet with his fiancée’s approval. Her letters had grown fewer latterly and one of his own had been returned stamped ‘unknown’. Junker was worried, but his work engrossed him. He painted his strange pictures and surrounded them with primitive frames of his own making. Later he even found collectors who were willing to buy his work: Herbert von Garren in Hanover and Paul Arndt in Berlin. There was a talk of commissioning Junker to sculpt a fountain for one of the squares in Lemgo, but this came to nothing. Already his relentlessly primitive and expressionist manner was beginning to upset people.

Shortly afterwards, his wife-to-be vanished without trace in Holland. Junker sank into despair. He went to seed, let his prematurely white beard grow and only left home to take occasional meals at the neighbouring Gaststätte. He had too much work in his house to attend to anything else. He had to carve – day and night – and he thought of nothing else.

Art critics of the day and, indeed, of our time have been baffled by Junker. What could so have obsessed the man to make him cover the exterior, the interior and the furniture of the house with thousands of carvings? Everyone who comes to Lemgo is staggered by the Junkerhaus, an unholy blend of the witch’s cottage in Grimms’ Fairy Tales, the hut of an African chief and the consulting rooms of Dr Caligari. Today nearly 10,000 visitors a year troop open-mouthed past the work of this German Picassiette – or Facteur Cheval, depending on your point of view. Every wall, chair and table has been covered with decorative elements and daubed with grey and blue paint. The carvings sometimes resemble bones, sometimes branches. You get the uneasy impression that you’ve stumbled into a catacomb in which everything has been petrified, preserved and applied by the hand of a maniac.

Karl Junker was indeed a mad genius. Twenty years of labour night and day; scores of maquettes of phantasmagorical architecture; 1,500 artworks stacked in the storage cellars of the Commune of Lemgo… All this is hardly the output of a conventional man. Some people have called his work the first great expressionist oeuvre – ‘a single project which unites the disciplines of sculpture, architecture and painting’. Others, like the psychiatrist Gerhard Kreyenberg, called the creations of the ‘Lemgo eccentric’ a classic example of the kind of art that proceeds from mental illness. Some claim that the region favours the growth of such fantasies, noting that Junker wasn’t the first of Lemgo’s oddballs. What about the famous Hexenbürgermeisterhaus, a Gothic building to which rumours of witchcraft still cling? And nearby Hamelin, with its surreal legend of the Pied Piper?

Luckily Junker’s house and his work survived the Nazi onslaught against ‘degenerate art’, the bomb attacks of World War II and the machinations of modern property speculators. In 1962, the Junkerhaus was purchased by the municipal authorities – only just in time.

Today the people of Lemgo still show a strong affection for the curious building and its former inhabitant, who is said to have encouraged local children to play in his garden so he could watch them from his window. One former keeper of the Junkerhaus claims that when his mother was a little girl she once took a tray to Herr Junker when he was sick in bed. Observing the fright in the child’s eyes, the strange old man said, ‘Don’t be afraid of me, little one. I have never hurt anyone.’

An old, rare photograph of Karl Junker taken just before his death in 1912 shows him with a maquette of his house. It’s an obvious hoax: the model has clearly been stuck on the portrait, as a montage. Yet somehow the picture tallies perfectly with the enigmatic character of this man ■

The Junkerhaus, 36 Hamelner Strasse, 32657 Lemgo, Germany. For opening times, ring 00 49 526 166 7695, or visit junkerhaus.de