The History of Landscape Design in 100 Gardens - Linda A. Chisholm

Indice

Queen Eleanor’s Garden

Winchester, England

Most marriages of the Middle Ages, especially those of kings and queens, were arranged for political and economic reasons. That was true of Eleanor of Castile’s marriage to King Edward I of England. But it proved also to be one of the great love relationships of medieval Europe. Perhaps one reason Eleanor was happy in Winchester was that she felt at home in the garden tended by gardeners from her father’s Spanish region of Aragon.

The Great Hall is all that today remains of the castle that along with the gothic cathedral dominated the town of Winchester in the Middle Ages. But its buttressed south wall and the later Christopher Wren buildings almost adjacent provide protection for the re-creation of the garden that once lay within the walls. In the 1980s historian Sylvia Landsberg designed and supervised the installation of the current garden in the triangle only ten by thirty yards in size. To enter is to go back in time to the thirteenth century.

The garden is named for not one but two Queens Eleanor who lived at Winchester. The first, of Provence, was the wife of Henry III. Their son Edward I may have expressed love for his Eleanor in the original castle garden. Here he may have told her of the coming crusade on which she chose to accompany him. Perhaps here he grieved her death in Scotland and planned the Eleanor crosses he would erect at each place the funeral cortege rested on its way to Westminster Abbey.

The fountain, the garden’s heart, sits in an octagonal pool from which a rill carries water to other parts of the garden. Eleanor of Castile must have remembered this Moorish garden feature from her childhood in Spain. Here a falconer might have shown his sport to amuse king and queen. The popular medieval diversion is honored in the fountain at Winchester. Patterned after a fountain in Westminster dated AD 1275, the placement of the bird of prey recognizes that he must dip his wings in water before beginning a hunting flight.

As a young woman, Eleanor might have waited on the turf bench hidden behind a wall of vines, enabling her to glimpse her suitor before he saw her. These benches or bankes, usually without backs, were cut into an existing hillock or made with a stone base, its hollow center filled with planting soil. The top was grass or, as often, chamomile which gave a pleasing scent when crushed. Behind the bench were often roses that also perfumed the air. At Queen Eleanor’s Garden the roses are red and white, presaging the symbols of the devastating dynastic Wars of the Roses between the houses of York and Lancaster in the fifteenth century.

A fair complexion was prized in the Middle Ages. The Queens Eleanor and their ladies found shade in the arbor, an oft-used feature of medieval garden design. Some were flat-topped, but others were basket vaults made of pliable hickory or willow to support roses, grapes, or other vines. The sides were free of plantings or, as at Winchester, enclosed to provide greater protection from the sun.

In addition to sight and scent, medieval gardens featured sound and movement. Rustling leaves, falling petals, gurgling fountains, and the rippling water of the rill were complemented by bird song and flight. Doves, used for food and fertilizer, cooed soothingly. A dovecote or columbarium provided a nesting place. These dovecotes were sometimes separate towers housing hundreds of birds, or they might be attached to a building on a wall or a roof.

Plantings at Queen Eleanor’s Garden reflect medieval taste. The turf includes Bellis perennis, a tiny daisy. There is a prized fig tree. Hedges are made of holly and hawthorn and border plants include basil, columbines, fennel, hyssop, irises, lilies, rue, sage, violets, winter savory, and wormwood. Possibly introduced by Eleanor of Castile’s gardeners are Mediterranean plants including hollyhock, lavender, and pot marigold. Ferns grace the shady corners.

Imagining the delight the original garden gave to the kings and queens, knights and ladies of the thirteenth century at Winchester Castle is not difficult in this well-researched and documented re-creation of a medieval pleasaunce.

San Pietro Abbey

Perugia, Italy

Most European gardens labeled as medieval are re-creations, only a few as carefully planned and researched as Queen Eleanor’s Garden in Winchester. Gardens reconstructed from plans, descriptions, paintings, or the findings of archaeology are rare. The monastery garden at San Pietro in Perugia, Italy, is one such garden where medieval plans in the library were confirmed by the work of archeologists from the University of Perugia which now owns the property.

From the late tenth century, Benedictine monks occupied the basilica and surrounding buildings, built as were antique Roman houses with rooms around a central open atrium. Four paths emanating from a central water well divide the garden into quadrants, a paradise form in which paths are substituted for Persian and later Islamic rills. Here the monks might have taken their daily charge from the book of Genesis which contains creation narratives shared by Judaism, Christianity, and Islam describing the Garden of Eden: “A river flowed out of Eden to water the garden, and there it divided and became four rivers… The Lord God took the man and put him in the Garden of Eden to till it and keep it.” The Garden of Eden was understood as the symbolic place where God speaks directly to man, bestowing blessings, giving directions, challenging excuses, and chastising for disobedience.

Medieval monks and nuns similarly hoped that in the monastery garden their prayers would be heard. So common did the paradise design become over many centuries that although today we may not always be aware of its original meaning, it remains an iconic form to this day.

At San Pietro, as in other monasteries, a covered walkway surrounded the interior garden and water source. A common pattern was to have a chapel at one side of the square, open from the interior cloister to the monks and with an external door for visitors. A second side served as chapter room where the monks met to conduct their business and, adjacent, the library of manuscripts. The monks’ individual bedrooms, called cells, were located on a third side. Completing the square or rectangle, the fourth side accommodated the refectory, visitors’ rooms, and the all-important hospital.

The paradise garden form in the cloister is only one of many symbolic designs at San Pietro. The zodiac garden was found by university archaeologists. At its center a tree grows from a spring that flows outward in four directions, representing the four liquids essential to life: milk, water, wine, and honey. In the zodiac garden the “heavens” are bounded by stones and low hedging, the beginnings of the parterre or ornamental garden with paths between the beds, a feature that was to become more elaborate with time.

Behind the cloister are raised beds for vegetables and herbs, as was the medieval custom. The pergola may have supported grapevines, climbing vegetables, or flowers. A large Roman marble basin or servatorium, perhaps once in the center of a Roman atrium, was used to keep fish fresh until it was cooked. Herbs used to dye cloth, to lay among clothes and on floors for fragrance, and to enhance the flavors of food are among the plants that would have been in the medieval garden and that are in the garden of San Pietro today. Even poison had its place, especially the black hellebore, said to be effective in killing the dreaded wolves. Above all, the physician-monks grew medicinal herbs, knowing what to plant and how to use them from the books of Dioscorides.

The sundial was another medieval garden feature, helping gardening monks know when to set work aside and gather in the church for the daily offices. These prayers were offered eight times daily according to the rule of Saint Benedict who adapted for the monastery at Monte Cassino the Jewish practice of prayer at set intervals of the day. Benedictines in Perugia and monks and nuns elsewhere continue the practice today.

Prieuré Notre-Dame d’Orsan

Maisonnais, France

Brothers of the Priory of Our Lady of Orsan in central France would have gathered each August to celebrate Saint Fiacre’s Day. The man who became the patron saint of gardeners was a seventh-century Irish monk whose healing powers drew so many to his door that he beseeched the bishop of Meaux to give him a new home with greater solitude for contemplation and prayer. Legend has it that the bishop offered him whatever forestland he could surround with a furrow in one day. Strong from gardening, Fiacre was able to uproot trees and bramble bushes to encompass a nine-acre plot. On the land he built a solitary hermitage for himself, planted a medicinal herb garden, and established a hospice for travelers. After his death in AD 670, he was canonized.

From the tenth to the fifteenth centuries the monks of Prieuré Notre-Dame d’Orsan in central France were, like Fiacre, skilled gardeners. The growing of vegetables, fruit, medicinal and culinary herbs, and flowers, especially roses, was their vocation second only to prayer.

As in other medieval gardens, water was located at the garden’s heart. At Prieuré Notre-Dame it emanates from a square fountain at the center of a paradise form, convenient for irrigating the surrounding herb, vegetable, and flower beds, the orchards, and vineyards. Radiating paths are formed by turf, highly prized in the medieval garden. Twelfth-century French cleric Hugh of Fouilloy expressed the popular belief that the color green, a symbol of rebirth and everlasting life, “nourishes the eyes and preserves the vision.”

As they watered, the monks surely meditated upon the religious truth symbolized by water, expressed in this fourteenthcentury poem by Guillaume de Machaut which likens the fountain to the Trinity:

Three parts make up a fountain flow

The Stream, the Spout, the Bowl.

Although these are three, these three are one

Essence the same. Even so the Waters of Salvation run.

Wood was readily available from the nearby forest and used for every possible purpose. Arbors supported grapes and roses. Low boards contained the raised beds. Palisade fencing formed by closely planted saplings that grew together as a solid and living fence protected the whole from rooting pigs and digging dogs. Wattle fencing, fashioned by driving stakes into the ground at intervals and weaving through them flexible apple shoots or young hickory, hazel, or willow branches, made the garden rabbit-proof. Slender poles gathered at the top like teepees provided support for beans and other climbing vegetables and vines. To prevent rotting, vegetables were lifted from the ground with low wattle domes.

Where town, castle, and monastery gardens were enclosed, the space for growing plants was limited. Gardeners developed a variety of techniques for making the most of the space they had. Trees and shrubs were pruned as pillars, cones, globes, pyramids, and obelisks so as not to block the sunlight. Topiary, the garden technique of pruning shrubs into unnatural forms, has been employed since the time of the Romans. Planting beds were edged with low-cut boxwood, germander, hyssop, lavender, rosemary, or santolina, creating rudimentary parterres.

Wooden frames on which fruit was trained assumed various shapes and sizes. Fruit trees were planted on either side of a path, then bent and lashed together, or pleached, at the top so that they grew together. Forming an arch, the pleached trees did double duty by producing fruit and providing a shaded walk. Another space-saving technique was to espalier fruit and berries, pruning the branches or canes to make flat patterns against a warm wall or as a fence, a practice that has stood the test of time. Orchards were all-important in the medieval garden as fruit was available only if locally grown.

Orchard trees were often planted in a quincunx pattern with four at the corners of a square and a fifth tree in the center. The pattern is repeated in such a way that all adjacent trees in the orchard are equidistant one from another. Quincunx, used extensively for mosaics and pebble floors and on coins in ancient Rome, was invested with religious and astrological meaning in the Middle Ages. Another essential to any medieval orchard was the apiary for bees. Gardeners understood the role of bees in pollinating fruit and so bee-keeping was an important part of every gardener’s job.

Quincunx was not the only pattern for planting. Mazes with their maddening dead ends were planned for amusement and games; the labyrinth, not hard to follow and leading always to the center, became the means for a spiritual journey. At Prieuré Notre-Dame high concentric hedges define the paths beside which pears, quince, grapes, and herbs fill the beds. Rhubarb grows tall within cylindrical wattle frames.

Of all the metaphysical symbols in the medieval garden, none was richer in meaning than flowers. In enclosed gardens a particular kind of flower was planted singly or at least sparsely, never massed. These flowers were often pictured in medieval paintings and tapestries, perhaps most famously in the Unicorn Tapestry in which flowers encircle the mythical beast. All one hundred plants that have been identified were woven with remarkable detail and accuracy.

Medieval literature and paintings depict time and again the flowery mead, or meadow, where a mixture of wildflowers abound. The mead at Notre-Dame d’Orsan is a riot of color, but all with delicate textures and shapes. Of all the flowers, the rose was the most loved and honored. In Greco-Roman culture the rose had represented the season of spring and of love. But the piety of the Middle Ages acknowledged the virginity of Mary by giving her the title hortus conclusus (enclosed garden), and the rose became her symbol.

John Whipple House

Ipswich, Massachusetts

When Thomas Jefferson developed his ideas of the ferme ornée he began with the several and varied traditions of American colonial garden design that were both utilitarian and decorative. John Whipple House is an early example of the utilitarian.

New England winters were harsh. When the baby came down with whooping cough in the middle of a seventeenth-century January night, it was critical that his mother had grown and dried scarlet pimpernel. All summer she would plant, tend, and harvest this and other medicinal herbs to prepare potions to cure the diseases winter was bound to bring. And she needed her garden near the house, enabling her to keep an eye on both baby and stew pot as she planted and weeded. Practicality, not aesthetics, was the prime consideration for those carving a living out of the wilderness.

The earliest American settlements were forts, evolving eventually into fortified communities. Only after many years—a century in some locations—was it possible to let down the guard and enjoy a relatively safe and peaceful existence. Only then were flowers and other ornamentals introduced. Some, such as the useful and attractive calendula, feverfew, pot marigold, tansy, and gallica rose ‘Apothecary’, fulfilled both criteria.

Captain John Whipple built the first rooms in his Ipswich, Massachusetts, home in 1677. His son and grandson each made additions until, with fourteen rooms, local residents called it “the Mansion.” Medicinal and culinary herbs interspersed with flowers occupied the beds in the front of the house. Sweet-smelling lilacs, able to withstand cold weather and biting wind, framed the front door at John Whipple House then as they do today.

The vegetable garden and orchard were also planted near the house, customary in most colonial American gardens for practical reasons. The housewife’s or kitchen garden as it was variously called was located in the front, back, or side yard depending on the house’s orientation to the sun and other conditions such as wind or ocean spray. The land was cleared around the house for some distance since dangers lurked in the forest. Seeing hostile Indians from a distance allowed time to bolt the doors and load the musket.

Fences encircled gardens to protect from hungry animals, wild or domestic. Split timber was the available material. Building upon memories of England, the colonists laid out their gardens geometrically, often using the paradise form with quadrants around a central point. Paths of gravel or crushed shells gave easy access to the planting beds. Colonial gardens such as that at John Whipple House were the beginning of the ferme ornée in America.

Munstead Wood

Surrey, England

Munstead Wood was Gertrude Jekyll’s haven, her home, laboratory, and studio. Here she perfected the art that brought her commissions, fame, and a lasting place in the history of landscape design. Here she designed and planted an herbaceous border, formulated her beliefs about seasonal beds, and learned how to make the transition from garden to woods. Here she would live from the house’s completion in 1897 until her death in 1932.

At Munstead Wood she wanted to achieve comfort, simplicity, and the quiet she needed to work effectively. She also wanted the values of the Arts and Crafts movement to be evident. The house, designed by Edwin Lutyens, is constructed of warm honey-toned Bargate sandstone available nearby, dark old timbers, and weathered roof tiles. Casement windows enhance the impression of age. A modest entrance and small courtyards with ironstone cobbles create the “cottage in the woods” for the “serenity of mind” she sought. Munstead Wood has been described as having the feeling of a convent, and so it does, just the place for contemplation and concentration, just the place for an Arts and Crafts artist.

On the north side of the house is a courtyard, enclosed on three sides by the house, the fourth side opening onto the garden. Above the Lutyens-designed and Lutyens-named bench hangs a swag chain for Clematis montana echoing the lines of the visible timbers. Jekyll believed that water in the garden is essential, whether in a formal or natural shape. At Munstead Wood the pool is simple like the plantings that surround it, its geometry conveying the order and peace that she desired.

Studying the life cycle of plants in Surrey, Jekyll became convinced that it is impossible to have a garden bed that is beautiful in all seasons. Rather she advocated seasonal beds that put forth a magnificent display for a few weeks and then recede as a focal point, being allowed to rest, decay, and die before their resurrection. It was a lesson learned from observing plants and one compatible with her religious convictions about human life.

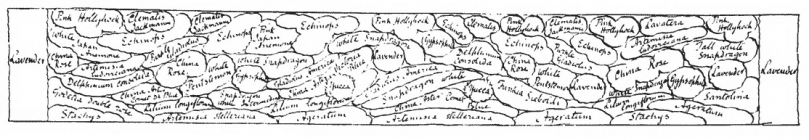

Parallel to the house in the lower garden is her herbaceous border, two hundred feet long by fourteen feet wide. Here she employed the techniques that would secure her fame as a border designer. The color scheme she had learned from studying the paintings of J. M. W. Turner: hot colors of red, yellow, and orange in the middle, cool lavenders, grays, and soft pinks at the ends, enlivening white throughout. Tall flowers next to the eleven-foot Bargate stone wall, itself adorned with flowering shrubs and climbers, were planted on earth mounded to make them appear even taller. Ground-hugging plants formed the border, and middle-height flowers held place in-between. Plants were grouped in clumps or drifts as if they were growing naturally. She used perennials and annuals, plants native to the region, and exotics, a favorite being yucca.

At Munstead Wood Gertrude Jekyll developed one of her greatest design interests and skills, that of linking surrounding woodlands with the garden. She generally positioned the more formal and geometric features—walls, pools, and flower beds—near the house with the wilder or natural elements such as woodlands and ponds farther away. When she purchased the Munstead Wood property it was semiwoodland with Scots pines, Spanish chestnuts, oak, and birch trees. She planted woodland bulbs such as snowdrops under the trees in a scheme that used many near the house and at the woods’ edge, then more sparsely as the trees were more dense. From the woods to the garden each few steps found the plantings more clearly those of garden rather than woods. Paths were made of materials that would naturally occur in the woods.

Gertrude Jekyll lived by herself at Munstead Wood, but she was rarely alone. Her mother lived a short walk away on adjoining property and when she died, Gertrude’s brother Herbert moved with his family into the house. Other Jekyll siblings visited with their children who, as adults, affectionately remembered their famous aunt. Friends including luminaries William Morris, William Robinson, and Ellen Willmott were guests. Her dear friend, collaborator, and architect for Munstead Wood, Edwin Lutyens, came often with his family. And she was never bored. In the garden that she had begun soon after purchasing the fifteen-acre property in 1883, she was always studying new plants and their habits and developing her ideas about the aesthetics of a garden. In her herbaceous border, her seasonable beds, and the transitions from woodland to garden she developed the garden design features that are synonymous with her name.

Upton Grey Manor

Hampshire, England

When Charles Holme retired from the wool and silk trade in Asia, he founded what was to be the most important magazine of the Arts and Crafts movement, The Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art. He also bought several properties in the charming Hampshire town of Upton Grey including the fifteenth-century manor house. He hired architect Ernest Newton to make extensive renovations and alterations to the Tudor house. Gertrude Jekyll, sharing as she did Holme’s Arts and Crafts sympathies, was the obvious choice to be landscape designer.

All of this was unknown to John and Rosamund Wallinger when they bought the manor house at Upton Grey in 1983. Having had six owners in the years between Holme’s ownership and theirs, the house and surrounding gardens had become derelict and even the villagers had forgotten the manor’s distinguished past. The Wallingers knew only that the house was listed on the national register of historic buildings. Research identified owner and architect but nothing about the gardens. Then Rosamund came across an intriguing footnote in a document related to the house: “Garden possibly by G. Jekyll.” She knew little about Jekyll except that she was a famous gardener. Dogged research produced the information that Jekyll had indeed designed the gardens at Upton Grey and that her plans existed. With the news, the Wallingers realized that under the out-of-control vines, brambles, and stinging nettles there lay a national treasure.

The University of California Berkeley owns the Gertrude Jekyll papers including the plans for Upton Grey. When a copy of Jekyll’s detailed plan arrived at last with every plant and its location identified, the Wallingers began restoring the disconsolate gardens to the glory they had once known. Faithfully following Jekyll’s directions, they recreated what is now recognized as the best restored of all the Jekyll gardens. It illustrates Jekyll’s planted walls and terraces, gentle steps, a sunken garden, herbaceous borders, and even a wild garden, all features for which Jekyll was known, as well as her wizardry in making a garden appear to have a venerable history.

When Jekyll began her planning for Upton Grey Manor there was a long and steep bank in front of the house. She hated banks. She would obliterate this one, creating at the lower level a sunken garden nearest the house with an adjacent turf area for bowling and lawn tennis. Terraces were supported by dry stone walls that she planted generously with more than twenty kinds of plants, among them alyssum, anemones, antirrhinum, arabis, arenaria, buxus, centranthus, dianthus, hemerocallis, irises, penstemons, poppies, sedums, and veronica.

The steps leading from the house to the lower garden were crucial to the success of the design. They had to be inviting, not daunting, a need for which she may have been especially aware at Upton Grey as she was herself in her mid-sixties when designing the gardens. She made the risers as short as possible and the treads as wide as the space allowed. When faced with the same challenge at other sites, she included landings to provide a place to pause.

Jekyll’s sunken, formal garden has only straight lines. On each side in the center of the space is a two-tiered square stone structure, replete with rock-hugging plants, moss, and lichens to enhance the impression that the structures are as old as the Tudor beginnings of Upton Grey Manor. Trapezoidal flower beds on each side frame the scene.

Throughout the gardens Jekyll put her artist’s eye to use. Did she think of Turner’s paintings when she planted the borders with the hot colors in the middle and cool grays and lavenders at the ends, or had the practice become so much a part of her work by this time in her life that she no longer consciously recalled its source? Did her spot of red, especially at the front of a border to draw the eye, remind her of John Constable whose paintings she had copied so many years before while in art school in London?

Sundials were favored by Jekyll as a garden ornament. They served as a focal point. They acted as a useful reminder to the tarrying gardener before wristwatches were made to withstand the moisture of the garden. And they were a means of teaching gentle moral lessons, bearing as they did maxims in Latin, English, French, or German such as “Count only sunny hours,” “Trifle not, thy time is short” and “Lead, kindly light.”

The borders and beds of Jekyll-designed gardens rarely had empty spaces, despite the natural life cycle of plants that die back after blossoming. She achieved this perfection in two ways. Anticipating the time each plant would go dormant, she planted something nearby that would be coming into bloom after its neighbor was spent. Hostas, she advised, are just the thing for hiding the dying leaves of bulbs. And she always had pots of plants on the verandas and in the courtyards that she could press into service when needed to fill in blank spaces in the borders.

Jekyll countered the formal garden at Upton Grey with a wild garden that by the Wallingers’ time would be the only surviving and faithfully restored example of this type by Jekyll. Iron gates, a stone apron, and grassy steps in a semicircle provide the transition from formal gardens and house to the planned natural wild garden. Mown paths wind through the plantings of taller grasses, rambling roses, shrubs, bamboos, and trees until ending at the pond, itself surrounded by artfully placed rocks and water-loving plants. Cowslips oxlips, primroses, and snowdrops were the flowers in the woods and fields Gertrude roamed as a child with her brothers: these she planted with anemones, fritillaries, muscari, and scilla in the wild garden at Upton Grey, these the Wallingers have faithfully and skillfully restored.